Lauren S. Grider, DVM, CCFP

Sydney* is a 41-year-old credentialed veterinary technician with more than twenty years of experience in the field. She typically works 40-50 hours a week at a busy small animal specialty practice, and she loves her job despite the high level of stress. Recently, her 10-year-old son was diagnosed with a chronic illness, and the treatment requires significant time, travel, and expense. Sydney has been burning the candle at both ends to continue working her normal schedule while providing extra care for her son. However, she is quickly reaching a breaking point. Her job’s long hours and relatively low pay are not meeting her needs, and something must change.

Historically, Sydney was willing to make monetary and time sacrifices to stay in her current role because she believes she makes a difference at work and wants to help animals. But now her son needs her, and she must find a more flexible and lucrative job. The problem is that she doesn’t know what else she would do, and she hasn’t been through a job search for over a decade. She also feels guilty for considering a career change when the office is already short-staffed, and she is mourning the loss of a career which has formed a large part of her personal identity for decades. Leaving her current position is the most obvious answer, but Sydney feels stuck. What can she do?

Career as an Identity

It is not uncommon for individuals, particularly those in demanding fields, to define themselves by their work.1 Work is viewed not only as a means of economic production, but also as a centerpiece of one’s life purpose, taking priority over relationships, self-care, and personal fulfillment.1 The danger of this mindset is career enmeshment, in which personal and career identities become fused and work boundaries are blurred.3 When a career makes up too much of an individual’s identity, disconnection from work can lead to problems like depression, anxiety, substance use, and loneliness, regardless of the reason for the disconnection.3

However, our core selves are not work-driven – they’re self-driven.1 Taking time to identify a unique personal purpose can help put what matters most in perspective. These priorities form the core self and help shape long-term goals.1 In turn, keeping long-term goals at the forefront of our minds can help us select and prioritize short-term goals and reduce anxiety.1

Understanding the Core Self

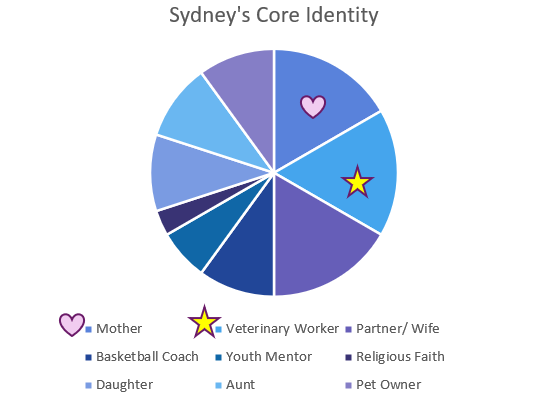

Creation of a core identity pie chart can be helpful in forming a picture of all the important identities that make up a person’s sense of self.4 Seeing the core elements of identity in a tangible form can improve self-understanding and illustrate that we are not one-dimensional beings. To make a core identity pie chart, simply draw a circle and divide it into portions that represent all the different traits and roles that are central to who you are. For example, when asked to draw a core identity pie chart, Sydney might create the following graph:

Now that Sydney can see all her meaningful roles on paper, the idea of changes in her career becomes less overwhelming. She can see that her identity is not one-dimensional and that she will not lose it if she steps away from veterinary medicine for a while to help her child.

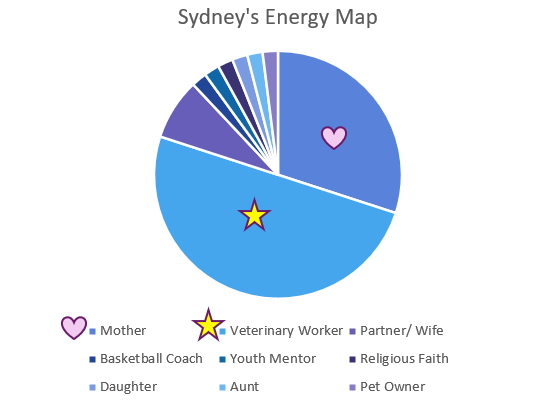

Sydney can also take the exercise one step further by creating an energy map. For this exercise, she would create a pie chart to indicate how her time and energy are currently being spent. She can then compare her energy map to the graph of her core identity and look for major differences. If a role is taking up a significantly bigger piece of the energy map than the core identity map, that’s a signal that adjustments need to be made so that Sydney can use her time and energy in the most fulfilling ways.

In Sydney’s examples above, it is clear that her role as a veterinary worker (indicated by the yellow star) is taking up significantly more of the energy map pie chart than the core identity pie chart. This is an indication that there is an incongruence, or mismatch, between Sydney’s priorities and how she is spending her time and energy. There is also an incongruence in Sydney’s role as a mother (indicated by the purple heart), as more of her energy is currently being devoted to that role. In these cases, self-reflection is needed to determine whether mismatches are acceptable or even desirable in the short-term.

After reflecting on this exercise, Sydney decides that her current work role is occupying too much of her time and energy given the other circumstances in her life. Additionally, she determines that the increased energy requirements for her role as a mother are expected and appropriate given her son’s illness. This information helps Sydney feel more secure about her decision to change her work role to make more time to care for her son.

Now that she is feeling less anxiety and guilt surrounding the idea of a career change, Sydney needs only to determine what other sorts of work roles she would enjoy and what types of jobs she is qualified to do. In the next article, we will help Sydney explore employment opportunities and learn about some excellent career building resources.

*Name changed to protect anonymity.

This article is the first in a multi-part series. Part two will focus on exploring new career opportunities.

References

1. Davis J: You are not your work. Psychology Today, 2019: https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/tracking-wonder/201903/you-are-not-your-work

2. Morgan K: Why we define ourselves by our jobs. Worklife, 2021: https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20210409-why-we-define-ourselves-by-our-jobs

3. Koretz J: What happens when your career becomes your whole identity. Harvard Business Review, 2019: https://hbr.org/2019/12/what-happens-when-your-career-becomes-your-whole-identity

4. Cox T: Developing Competency to Manage Diversity: Readings, Cases, & Activities, 1997. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________